|

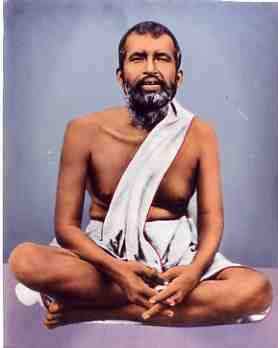

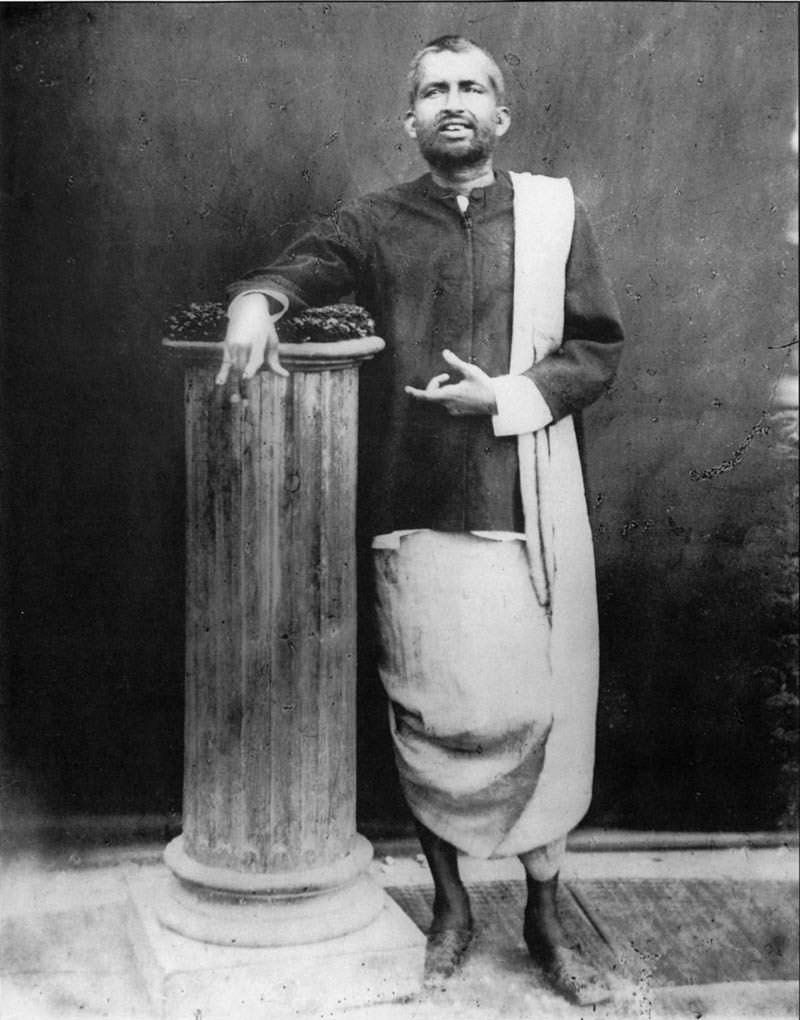

Ramakrishna Parmahamsa:

Ramakrishna Parmahamsa is perhaps the best known saint of nineteenth century India. He was born in a poor Brahmin family in 1836, in a small town near Calcutta, West Bengal. As a young man, he was artistic and a popular storyteller and actor.

His parents were religious, and prone to visions and spiritual dreams. Ramakrishna's father had a vision of the god Gadadhara (Vishnu) while on a religious pilgrimage. In the vision, the god told him that he would be born into the family as a son.

Young Ramakrishna was prone to experiences of spiritual reverie and temporary loss of consciousness. His early spiritual experiences included going into a state of rapture while watching the flight of a cranes, and loosing consciousness of the outer world while playing the role of the god Shiva in a school play.

Ramakrishna had little interest in school or practical things of the world. In 1866, he became a priest at a recently dedicated temple to the Goddess Kali located near Calcutta on the Ganges River. It was built by a pious widow, Rani Rasmani.

|

They concluded that this was a case of divine madness similar in nature to that of other famous saints such as Caitanya (a fifteenth century Bengali saint). From this point on, people began to treat Ramakrishna with more respect though his unusual behavior in worship and meditation continued. The holy women stayed with Ramakrishna for some time teaching him yogic and tantric meditation techniques.

|

|

|

A yogin named Totapuri then became Ramakrishna's mentor. Ramakrishna adopted the role of renunciant and learned a nondualist form of Vedanta philosophy from him. In this system, God is understood to be the formless unmanifest energy that supports the cosmos. Ramakrishna experienced a deep form of trance (nirvilkalpa samadhi) under the guidance of this teacher.

This state can be described as complete absorption of the soul into the divine ocean of consciousness. Disciples began to appear at this point in Ramakrishna's life. He embarked on a long period of teaching where he gathered a group of disciples around him.

This period of his life is well documented by two sets of books written by his disciples. These references are listed below. Ramakrishna explained on different occasions that god is both formed and formless and can appear to the devotee either way.

|

These devotees saw him as a great teacher and bhakta who sang the names of God and talked incessantly about God. They too did puja and sang Kali's name in hopes of having healthy children, getting good jobs or marriages, or producing a plentiful harvest. The sincere devotee could even hope for a vision or dream of the divine mother.

|

|

|

Ramakrishna and Psychological Reductionism

An unusual development in modern attempts to understand Ramakrishna’s life has been the recent application of psychoanalytic theory to his experience. While a large majority of psychologists consider psychoanalytic theory to be discredited, historians of religion have resuscitated this moribund methodology in an attempt to explain the existence of Ramakrishna’s mystical experience.

Specifically, it is claimed that Ramakrishna's mystical states (and through generalization all mystical states) are a pathological response to alleged childhood sexual trauma.

There are, however, some serious problems with the attempt to apply this form of psychological reductionism to Ramakrishna. First, the most recent proponent and popularizer of this theory is not a psychologist and has no formal training in psychoanalytic (or any clinical) theory.

|

Second, he is doing his analysis based on a set of biographical texts rather than direct contact with an individual patient in a clinical environment. Psychoanalysis is a highly interactive process, and analysis of textual data cannot begin to approximate the complex and detailed information provided by the one-on-one relationship that develops between patient and analyst. Applying the psychoanalytic method to one or more texts about a person is therefore likely to result in a failure to understand the patient.

Third, the author is working in a thoroughly non-western culture where is it highly questionable whether Western psychoanalytic theory even applies. Fourth, the author has been shown to have difficulty understanding the nuances of the Bengali culture in general as well as the Bengali language in which Ramakrishna's biographical texts are written. He spent a mere eight months in West Bengal most of it apparently in libraries and on this basis makes grandiose claims about understanding both the mind and cultural environment of the renowned saint. This limited exposure makes him subject to serious errors in translation and to misinterpretation of both cultural and textual data.

The fact that many historians of religion have eagerly embraced this antiquated Freudian methodology in an attempt to understand Ramakrishna and mystical phenomena in general is an indication that the field may be in trouble. Historians of religion and those in the field of religious studies who grant awards to books based on cultural and psychoanalytic illiteracy seem to be at a loss to find a better methodology by which to understand saints and their religious experience.

|

|